|

Table of Contents Introduction: About the Author and Book Introduction: A Brief History of Personal Power What Makes This Book Unique The Five-Circle Model of Personal Power Part I — Lessons to Enhance Your Power with Others Lesson #1: Principles Fortify and Empower You Introduction: The Enron Scandal Blowing the Whistle Intolerant Views Falsifying Elections Principles and Fortitude How Principled Are You? A Flag Burning The Illusion of Moral Superiority The Field Experiment The Effect of Honor on Power Other Predictors of Power Your Philosophy of Work or Life Endnotes for Lesson #1 Lesson #2: Empower Others to Empower Yourself Introduction: Silver Empowerment The Power of Empowerment Formal Empowerment Informal Empowerment The Politics of Compliments Suggestions for Empowering Others The Reciprocity Rule Endnotes for Lesson #2 Part II — Lessons to Prevent You from Losing Power Lesson #3: Envy, Loyalty and Greed Trump Principles Introduction: The Halliwell Tragedy Envy and Power How to Tamp Down Envy Acknowledge Your Envy Focus on Your Strengths, not Others Stay Clear of Envious People How to Deal with Envy on a Team Loyalty and Power The Power of Loyalty Over Principles The Consequences of Doing the Right Thing Greed and Power The Origins of Greed How Can Greed be Controlled The Neighborly Deeds of Neighborhood Ventures The Talented Timothy Springer Endnotes for Lesson #3 Lesson #4: Don’t Gossip or Talk Politics and Religion Part III — Lessons to Protect Yourself from Adversaries Lesson #5: How to Deal with Bullies and Mean Bosses Lesson #6: Never Overestimate Morality of Adversaries Part IV — Lessons to Protect Yourself from Your Organization Lesson #7: Organizations Emphasize Control, Not Freedom Lesson #8: The Bigger the Organization, the Greater the Conflict Lesson #9: Organizations Emphasize Winning over Morality FROM THE BACK COVER Puffed up bosses. Envious, backstabbing coworkers. Workplace bullies. This book -- 9 Lessons of Personal Power: Why Some People Thrive in the Workplace and Others Don't -- helps working professionals acquire and wield power to control these miscreants as well as enhance their personal power through everyday interactions with congenial colleagues and bosses. Enduring power comes not from domination but from moral principles, honor, empowering others, and leveraging resources in the organization and society. 9 Lessons will show you how to:

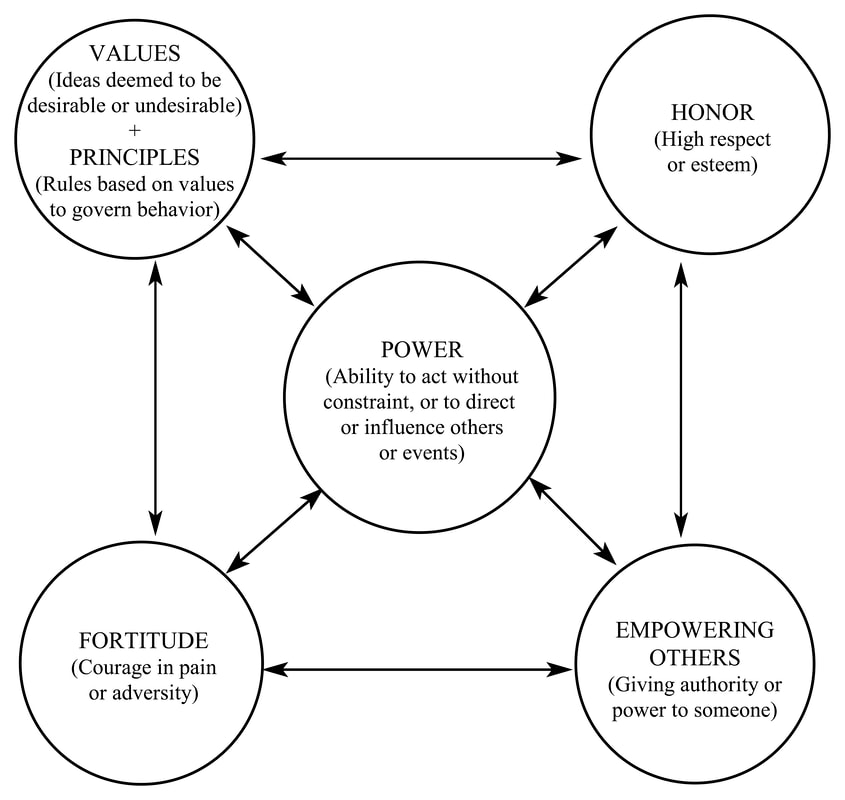

Like other books on personal power, this one is grounded in science and is extensively documented. This book also uses lots of examples and stories to illustrate concepts and ideas, and it examines the psychology of power in the workplace. Dr. David Demers worked as a journalist, market research analyst, professor and professional ghostwriter. He has written more than 20 books, including a dozen scholarly books on power and social structure. He ghostwrote the best-seller ABCs of Buying Rental Property: How You Can Achieve Financial Freedom in Five Years for Scottsdale entrepreneur Ken McElroy (600+ Amazon reviews in less than two years, 4.7 overall rating). He earned his Ph.D. from the University of Minnesota (in mass communication and sociology) and was a tenured professor at Washington State University for 16 years. He also taught at the University of Wisconsin-River Falls, University of Minnesota, and Arizona State University. Figure 1. Five-Circle Model of Personal Power |

About the Author and Book [From the Introduction. Note that the endnotes are excluded from this text.] As a kid, I was never adept at acquiring and wielding power. I was born into a working-class family, not a wealthy one. My parents never talked about money and power at the dinner table, nor did they hang around with the powerful people in our small Michigan town. My Lutheran elementary school teachers taught me and my fellow students that power was something reserved for God, not humans. They instructed us to be kind, deferential, honest, compassionate, and respectful — traits that stand in opposition to power, according to many classic and popular works. I was never the leader of a club or captain of a sports team. I only made it to First Class in the Boy Scouts, three ranks below the prestigious Eagle. In high school I was the third-smallest boy and a favorite target of bullies, one of whom picked me up by my neck, pinned me against the wall, and laughed as I struggled to breathe. When it comes to power, size matters, at least when you’re a kid. But my relationship with power improved after I entered college. I created an independent student government office to disseminate information about campus issues and the war in Vietnam. When I discovered that the student body president and other officers had illegally withdrawn several thousand dollars from a student fund to pay for their college expenses, I blew the whistle. As a newspaperman, I never made it above the rank of editor, but I did have some power to uncover abuse of power. I exposed a chemical company whose landfill had been leaking carcinogenic chemicals and discovered that state investigators had used shabby evidence to prosecute the owners of an adult foster care home. In graduate school, I majored in sociology, a field that has produced a lot of knowledge about power. I was intrigued with the 1956 book The Power Elite, in which C. Wright Mills argued that power is concentrated in the hands of business people, political leaders, and top military brass — a controversial theory at the time. In the late 1980s, students in my news reporting class at the University of Minnesota confronted the power-elite problem when the Minneapolis Police Department refused to give them access to citizen complaints against officers. I filed a freedom of information lawsuit, and the Minnesota Supreme Court forced police to turn over the records. Students and I analyzed them and found that complaints filed by white people were twice as likely to be upheld as those by black people. As a professor of journalism and mass media sociology, I never made it to the rank of administrator, nor did I want to. I noticed that many professors who became administrators abandoned their democratic and free speech ideals as they adopted the perspective of their control-oriented institutions. These administrators and others often made decisions behind closed doors and punished faculty who criticized their policies. In fact, when I helped journalism students publish some controversial stories about faculty salaries and student evaluations, administrators handed me a pink slip. I filed a federal free speech lawsuit and they capitulated, paying me $64,000 to drop the case. Soon thereafter, I was tenured at Washington State University and thrived over the next decade. But when I created a plan to seek national accreditation and other improvements for my academic unit, administrators placed me on the “termination track.” Faculty don’t deserve free speech rights when it comes to administrative matters, they said. I disagreed, and so did a federal appeals court, which declared in a landmark ruling that the First Amendment protects all faculty speech related to teaching or scholarship, not just words uttered in the classroom or published in scholarly papers. As word of my activism spread, faculty from other universities and their attorneys would call, seeking my advice for their battles. I eventually wrote a memoir and offered 40 lessons for activists, journalists and professors. The central theme of that book was that journalists, professors and university administrators weren’t doing enough to promote democratic processes and free speech. Many readers, though, were less interested in the call for social justice than in the 40 lessons. So I began writing this book, which distills those lessons and others into a concise list of 9 applicable to a broad range of professional groups and workers. The goal of these lessons is to help you thrive in your organization, even if acquiring power is not one of your goals. You may not want to be the crab at the top of barrel, but you certainly don’t want to be the one pushed to the bottom, either. What Makes This Book Unique Like other books on personal power, this one is grounded in science. But unlike others, it’s also anchored in a lifetime of personal experiences. Although I’ve been fortunate to prevail against powerful organizations, individuals usually lose when they go up against big “collectives,” because they have deep pockets and resources like credibility, something ordinary individuals like you and me typically lack outside of our familial and friendship networks. Laws in America also generally favor employers over employees. Yet individuals can bring down Goliaths when they leverage resources available to them in their organizations and society. This includes both administrative or legal actions and simple things like aligning yourself with other powerful principled managers or leaders. Large, complex bureaucracies also have many shortcomings. They are slow to act and have weak commitments to moral principles, poor internal communication, ambiguous lines of authority, and managers who are risk-averse, fearing a mistake will cost them their privileged jobs. These shortcomings and others can work to your advantage. For most of you, though, your greatest adversary likely isn’t your organization or its upper management but the people you work with every day, some of whom enjoy throwing knives into your back. Like other books on power, this one scrutinizes the motivations and actions of coworkers, colleagues, bosses and managers. Psychology professor Dacher Keltner argues that many managers become more abusive as their power grows. He calls this the power paradox. “We gain a capacity to make a difference in the world by enhancing the lives of others, but the very experience of having power and privilege leads us to behave, in our worst moments, like impulsive, out-of-control sociopaths.” I’ll talk about some real-world sociopaths and show you how to protect yourself from puffed-up bosses and workplace bullies. Unlike other books about power, this one examines not just the psychology of power but the sociology of power, too. This means I’ll discuss the effects of things like hierarchy of authority, rules, division of labor, and organizational values and goals. Envy, for example, is a big problem in larger organizations. To solve the problem, an organization can try to change the attitudes of its employees (see Lesson #3 for suggestions), or it can create specialized roles in a department, which reduces competition between coworkers. Everyone becomes in expert in something, which boosts egos and reduces envy. This book also takes issue with some of the popular books on power which contend that, to gain power, you have to manipulate, bully, or deceive people. For instance, Robert Greene’s 48 Laws of Power advises readers to conceal their intentions, take credit for other people’s work, pose as a friend but work as a spy, play to other people’s fantasies, and seduce others into their (readers) worldview. Michael Korda’s POWER! How to Get It, How to Use It gives examples of the type of people who possess power: They throw their coat over a chair in your office to establish territoriality over you; they sit in front of a window so others have to look into the glare to see them; and they are never sentimental. Jeffrey Pfeffer’s Power: Why Some People Have It — And Others Don’t advises readers who want to grow their power, “You need to get over the idea that you need to be liked by everybody.” These books and others draw some of their advice from Niccolò Machiavelli’s 16th-century classic The Prince, which contends that fear is more effective than love for controlling people, at least when a leader cannot possess both. As an individual and a scholar, I concede that fear, deception and abusiveness can help people acquire and maintain power. Vladimir Putin won’t let us forget that. But misleading people or scaring them can backfire, as Hitler, Caligula, Mussolini, Gaddafi, and Saddam Hussein discovered. The lesson here is that power based on fear or deception is almost always unstable in the long run. In contrast, kindness and empathy are not only more stable bases for power, they are more effective, according to scientific research. At least 70 studies have found that competent leaders possess at least five major traits: (1) enthusiasm, (2) kindness, (3) focus (on shared goals and rules), (4) calmness, and (5) empathy. Research also shows that (6) empowering others, (7) integrity and (8) fairness are crucial. The history of great leaders such as Gandhi, Mother Teresa, Martin Luther King Jr., Nelson Mandela, and Jesus backs up these studies. My conception of personal power shares common ground with the leadership theories of Professor Keltner and consultant Blaine Lee. Keltner argues that power comes from respect, humility, generosity, and empowering others. Lee adds that honor (respect or esteem from others) is more important than dominance: “True and lasting power doesn’t stem from ... intimidation. ... The key to power ... is honor.” And honor, in turn, comes from morally grounded values and principles, such as empathy, honesty, integrity, and empowering others. These are the criteria by which leaders should be judged, not whether they toss their coat on your chair. (And if they do that in your office, tell them to hang it in a closet and remind them that their mother would be appalled if she saw them do that.) Morally grounded values and principles also fortify you. Fortitude gives you courage in times of pain or adversity. It gives you the strength to withstand abuse from vitriolic coworkers and mean bosses; it insulates you from caustic remarks, insults, gossip, rolling eyes, spiteful glances, and snickers — a topic I’ll take up in Lesson #1. Although most of us like to think we’re principled, my experience is that many people fail to live up to the ideal version of themselves, especially when they have something to lose or nothing to gain. When powerful managers falsely accuse subordinates of violating rules, for example, most co-workers turn a blind eye. Envy, loyalty and greed usually trump principles, as I will discuss in Lesson #3. A morally grounded set of principles is not just a path to honor and power — it can mean the difference between life and death. Workplace bullying expert Kenneth Westhues notes that many people who face heavy criticism at work end up suffering from depression. Some even commit suicide (I’ll discuss two cases in Lesson #1). But people who embrace a strong set of principles not only survive, they thrive. Their principles fortify them. If you doubt me, just recall the list of respected leaders I mentioned earlier (Gandhi, etc.). Every one of them faced extreme pain or adversity. Some were even killed for their beliefs. But we revere and honor them today because they stood firm on their principles and placed the needs of others before their own. This book also differs from most other books in terms of how its advice is framed. Other books often blame individuals for their powerlessness. To grow your power, they recommend that you change the narrative about yourself — stop thinking that you are unworthy or incompetent or an “imposter.” Nothing wrong with suggesting that people have positive thoughts about their abilities. But changing people’s opinions about themselves is not an easy thing to do. Few people wake up in the morning and declare, “I’m competent as hell and I’m not going to take it anymore.” Instead, I think a more productive approach is to give people concrete, actionable advice that alters their behaviors in small ways that, over time, will produce big paybacks. A good, simple example is offered Lesson #2. Offer sincere compliments to others for good things that they do and you will find that many will reciprocate, which empowers you. The Five-Circle Model of Personal Power The theory or model of power I’ve just briefly described is summarized in Figure 1, which has five circles representing the concepts of (1) power, (2) values/principles, (3) honor, (4) fortitude, and (5) empowerment. The circle in the center represents power, which is one of the goals most people pursue with varying degrees of effort. Not everyone wants to be a manager or top executive. But no one I know wants to be the kids on the beach who gets sand kicked in their faces. Power is not inherently evil or good. It depends on who benefits and who doesn’t. Parents have a lot of power over their children. When they chastise their children for crossing a street without first looking for cars, most of us would agree this is a good thing. The goal is to keep children safe. But when Putin’s artillery targets civilian areas in Ukraine, most of us see that exercise in power as evil. The type of power examined in this model is personal (or individual) power. Organizations also wield power. But my main focus is on how power affects you, the employee or manager, and how you can enhance or maintain your power in responsible ways. Power comes from many sources. One of the most important is from the organization itself, through the roles that link individuals to the organization. The president or chief executive officer has more power than managers and employers at lower levels. Your power with respect to others depends in part upon your relationship to the organization. When you leave the organization, you typically lose most of your power within it. Another big source of power is wealth, and one of the surest ways to acquire wealth is to be born to rich parents. In fact, more than half of the wealth in America is inherited, which means a lot of power is inherited, not earned. Research shows that tall and good-looking people enjoy higher levels of power. Education, too, is strongly correlated with income and power. But this book will not focus on sources of power over which most of us have little control. We can’t choose our parents or genes. I’m also not going to focus on power in the home or in friendship networks. A person may have a strong influence on family members but have no power in the workplace. The social dynamics are not the same, even though people who possess power in one setting often do so in others. My focus is mainly on the workplace, because power in that setting is often — too often — wielded in abusive ways. A recent poll by the Pew Center revealed, for example, that nearly 6 of 10 workers who left their jobs in 2021 did so in part because they “felt disrespected” at work. People who have power don’t feel that way. The four circles around the power circle in Figure 1 represent concepts that I will examine and that can enhance or lessen the power of an individual in the workplace. Values refers to ideas you believe are desirable and good or, alternatively, undesirable and bad. Good values generally enhance power; bad ones don’t. Empathy, for example, is a trait most of us value, because it promotes understanding of others. A principle is a value put into practice through a rule or belief. For empathy, this could mean a simple rule like I will listen to and try to understand the concerns of others. Most of us also value free speech but not anger, because it can lead to conflict and violence. Hence, we could create personal rules like I will speak up when people threaten the free speech of others and I will remain calm in stressful situations. We know from previous research that people who embrace a morally sound set of values and principles are more likely to be respected and honored by others. They also have more fortitude (see Lesson #1). And people who empower others, either through work-related tasks or simply through acknowledging their opinions and accomplishments, are more respected and typically enjoy more power than those who don’t (see Lesson #2). In turn, all four of these characteristics — values/principles, honor, fortitude, and empowerment — enhance an individual’s personal power. Of course, the more power people gain, the more likely it will feed back and influence the other four conditions as well. Although acquiring and maintaining power in the workplace can be difficult, you can make the process easier if you learn how to leverage your own assets as well as the resources in your organization and society. The 9 lessons that follow are designed to help you do that. I’ll begin with the single most important lesson of all: Principles Fortify and Empower You. The remaining 8 lessons are categorized under three headings: (I) Lessons to Enhance Your Power with Others (see the Table of Contents for details), (II) Lessons to Prevent You from Losing Power, (III) Lessons to Protect Yourself from Others, (IV) Lessons to Protect Yourself from Your Organization. Are you ready to power up? |