Chapter 1

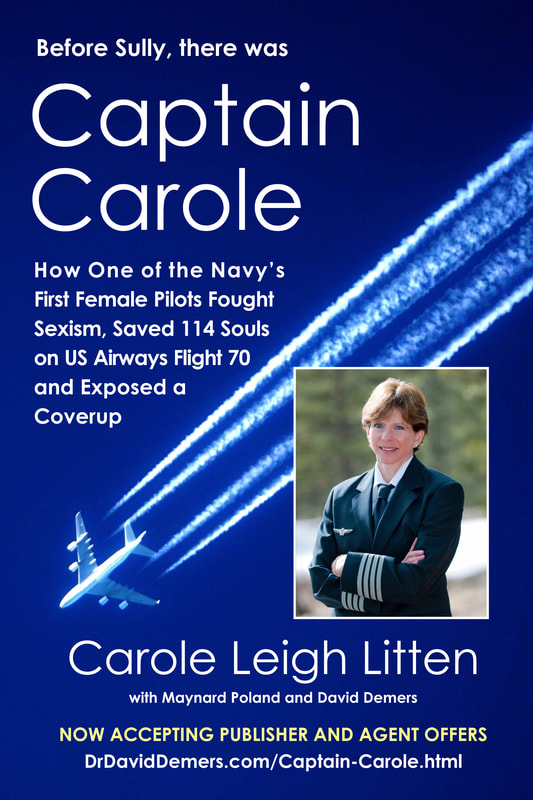

Fire in the Sky

10:20 a.m, Sunday, June 11, 2000

US Airways Flight 70

San Francisco to Philadelphia

Over the California-Nevada border

My copilot, Arnie, had just leveled our Airbus 319 to a cruising altitude 37,000 feet in a serene powder-blue sky when an alarm screeches and a red master switch flashes a warning message that the aft cargo compartment is on fire.

We glance at each other.

Is the warning light malfunctioning or is there a fire?

We have no access to the cargo area and it has no cameras.

We pitch our breakfast trays to the flight deck behind us, reach down on the outside of our seats, and extract and don our full face oxygen masks. My thoughts drift to the flash fires that brought down ValuJet and Swiss Air airliners several years earlier. All 339 passengers and crew aboard those two flights died. At this altitude, we would need at least 15 minutes to land the plane. A fire can do a lot of damage in that time.

From the captain’s seat on the left side, I swiftly raise my right hand and press an overhead panel button that activates the aft cargo fire extinguisher, which is designed to flood the room with Halon gas. I hold my breath, waiting to see if the warning light will go out. My heart is pounding faster than normal, but I feel no panic. I’ve been through hundreds of emergency drills before in simulators and a few real ones in the air. I’m 47 and have been a commercial airline pilot for eleven years. I learned to fly in the Navy and was one of the first women to earn her Navy Wings of Gold in 1980.

Arnie is cool-headed, too. Former Marine Corps pilots are like that. He gives me one of those let’s-hope-this-works looks. He’s in his forties and had been a Marine pilot for twenty years, including four years as captain of Marine One, the helicopter that ferried Presidents George H. W. Bush and Bill Clinton to and from the White House. Arnie has about a year’s experience as a commercial pilot. He’s piloting this leg of the trip.

The fire warning light finally goes out.

We remove our masks and take a deep breath, but the emergency isn’t over. The fire could flare again, so I instruct Arnie to “prepare to get the plane down.”

As he programs the autopilot for descent, I hail Oakland Air Route Traffic Control Center. “US Airways Flight 70 is declaring an emergency. We just extinguished a fire in our aft cargo but need to land.”

“Reno [airport] is the closest,” the control center responds. “Just off to your left and pretty much right below you — thirty-seven to forty miles away.”

“Okay, we’ll go there.”

“Turn left heading 3-4-0. Cleared to 24,000 feet.”

Arnie sets the descent at 6,000 feet per minute. That’s twice as fast as normal. Gravity is going to suck passengers forward against their seat belts, frightening some.

I push a call button, and Terri, the lead flight attendant, opens the door and leans her slim body toward me. “What’s up?” Her job is to keep the passengers calm, but I don’t want to alarm her, because she is a recently hired flight attendant and I don’t how she performs under stress. The lead flight attendant job is often given to lesser-experienced attendants, because the work load is heavier and experienced attendants feel entitled. So I soft-pedal the emergency to Terri.

“We’re making a divert into Reno to have the pressurization system looked at before going over the Rocky Mountains. We are going to descend quickly and the landing should be normal. Prep for landing.”

Terri is calm, and her simple, noninquisitive response — “I understand” — reassures me.

I brief the passengers over the intercom. “This is the captain. We are making a precautionary diversion to Reno — just off to our left — to have our pressurization system checked before flying over the Rockies. Sorry for the delay. It shouldn’t take long to check out our concern and get underway again.”

I stretched the truth a little. It likely will take a while to install a new fire extinguisher system, but my main concern is to prevent the passengers from panicking.

Arnie monitors our descent and I enter the code letters for Reno into the computer to obtain dynamic approach and landing feedback information. I’m concerned about the mountains on the west side of the airport, but the computer won’t accept my entry. So I pull out the Jeppesen approach plate book, which provides a visual representation of landing approaches at airports. Nothing there, either.

“Damn! Mountains and no approach plates. The airline must consider Reno such a poor divert alternative that they didn’t even include it in the binder.”

Arnie frowns. I don’t know whether he’s reacting to the lack of information about the landing approach, to my frustration, or both. This is my first trip with him. He is a man of few words. I like that.

I turn my attention to completing the approach checklist.

Air traffic control clears us to go to 11,000 feet, which is 500 feet above the minimum safe altitude to clear the mountains. Arnie then resets the autopilot to descend at 2,000 feet per minute. The approach to the airport is three minutes away.

But a minute later, at about 15,000 feet, a chime sounds and an amber warning light flashes on the panel: OIL FILTER CLOGGED. Before Arnie and I can process that message, another amber warning light appears: LOW OIL PRESSURE. Yet the oil pressure indicator gauge is green, not amber or red, which means that even if the filter is clogged, oil apparently is getting to the engine through a bypass.

Shit — two emergencies almost never happen at the same time.

“Arnie, what’s happening? The warnings don’t make sense.”

“Temps and pressures are okay,” he says. “No vibration, no unusual noise. Do you see anything, Carole?”

“Nothing you don’t. Maybe we could bring the engine to idle — keep it running in reserve for more power over the mountains if we have to go around for a second approach.”

Arnie’s dark brown eyes narrow. “Carole, my best guess is that the filter bypasses are clogged and the engine’s not getting oil. It’s telling us to shut it down so it doesn’t seize and explode.”

“Well, we’re not a thousand miles out over the ocean,” I say, thinking out loud, “and we’re so high and close that we more than have the field made, and we can fly single engine. Okay, let’s shut it down. Arnie, I know it’s your leg, but I’ll take the aircraft.”

“I agree we should shut the engine down.” He pauses. “Carole, you’re the captain, but I have a lot more time in the Airbus. Are you sure you want to take it?”

“Yeah, I’m sure.”

Arnie does have more time flying the A319 than I do. But I have far more experience flying commercial airliners, including the wide-bodied Boeing 767, and I have spent years instructing pilots in simulators and in the air. Besides, the captain is ultimately responsible for her airship. I’m not going to shirk my responsibility.

“Okay, Captain, you have the aircraft.”

We go through the shutdown procedure for the left engine. I guard the right engine power lever with my right hand. When pilots are under stress, they sometimes make mistakes. My job is to ensure Arnie doesn’t shut down the good engine. He grasps the left engine power lever, and we confirm three times that we are shutting down the correct engine.

I compensate for a slight yaw to the left that occurs when an engine is shut down. The transition is seamless, as if nothing had happened.

I call Reno Air Traffic Control. “This is US Airways Flight 70 declaring a full emergency. We had to shut down the left engine.”

“How many Souls on Board? And how much fuel?”

Controllers who use the term “souls” violate FAA guidelines, which recommends “people,” but this is no time to debate that point. A captain also is supposed to report fuel levels in hours of flight time, but I don’t have time to do the calculations.

“I have 108 passengers, six crew, and 40,000 pounds of fuel.”

“OK, you should see Reno right in front of you.”

Arnie and I had been too busy to visually locate the airport. Now I can see the far end of the runway, just beyond the crest of the mountain we are passing over. But the runway is still 6,000-feet below us.

“Oh shit!” I mutter. “We’re way too high.”

Arnie frowns again.

“Let’s sidestep,” I say, loosening my starched white collar. “I’ll reduce airspeed. Looks like no mountains at the north end, so we should be able to turn around and land going back south, the same way we came in.”

Arnie nods.

The airport has two parallel north-south runways. The one on the west, when landing south, is 17R and is 11,000-feet long. The east one is 17L and 9,000 feet. I want the west-side runway so I can see out the side cockpit window and use the east runway as a guide for landing. Besides, 17R is longer. We may need the extra space.

Arnie hails the control tower and requests 17R, but the tower wants us to use the left runway.

“No, we’re going right!” Arnie says firmly.

The tower concedes.

I smile. Nice to have a Marine as a first officer. During emergencies, ground control must defer to pilots. Reno’s responsibility is to clear the runway of aircraft and get the emergency vehicles ready.

I grasp the side stick flight control with my left hand and switch off the autopilot. Without computerized feedback about the airport, Arnie and I will have to decide on an appropriate airspeed and rate of descent. I manually adjust the rudder trim again to compensate for the uneven push due to flying on one engine. I lower the landing gear and flaps and begin doing S-turns to slow airspeed. No time to tell the passengers what’s happening.

My biggest concern is stopping the plane after we land. Fully loaded, the A319 needs about seven-thousand feet of runway, which is four thousand less than the length of R17. But we only have one reverse thruster to slow our speed, and we’re heavy with fuel. Will the tires hold up when we brake?

Our plane’s radar altimeter now shows we’re 2,300 feet above the ground.

“Arnie, ask them if there’s a VASI at the north end of the runway.” A visual approach slope indicator is a color-coded runway lights system that shows whether the aircraft is on the correct landing approach with the preferred three-degree glide slope.

“Yes, there’s a VASI,” the tower responds.

Arnie and I conclude that our best landing speed is 150 knots, slightly faster than normal, because we’re heavy with fuel and because we can only use 20 degrees of flaps instead of 30. At this weight, the drag with 30 would be too much and we’d have to use a faster landing speed. We don’t want to run out of runway.

Just past the north end of the runway, I make a U-turn and line up with 17R. VASI lights are red over white, indicating our glide path is perfect.

Runway coming up.

On centerline.

I can feel my heart pounding in my fingertips.

Touching down ...

* * * * *

A popular trope says your life flashes before you when you’re in a near-death situation.

Although I was confident I could safely land Flight 70, I couldn’t help but reflect for a moment on my past.

My childhood was difficult. I had a mother who often beat me and shut me into a closet; a brother who stabbed his psychiatrist and tried to attack me; and a cold-hearted father who refused to allow me to join him for Thanksgiving dinner one year. One of my mother’s boyfriend’s sexually abused me when I was a girl. When I was promoted to captain, my father never congratulated me. Perhaps he envied me, as he had only achieved the rank of commander.

My grandfather was one of the few loving people in my life. He had been a Navy pilot and admiral and had earned the Navy Cross for bringing to port his ship, the U.S.S. Kearny, after a German U-boat torpedoed it two months before the United States entered World War II.

My life in the Navy wasn’t easy in the early years. One enlisted man tried to rape me. Some superior officers made passes at me and stalked me. On three occasions men accused me of wrongdoing, including the heinous act of typing up Christmas carols on a base typewriter.

As a pilot in training, some male flight instructors tried to derail my career. “You’ll never be as good as we are,” one said. Another instructor shut down the hydraulic system on a plane during final approach in an attempt to prove that I — at 5-foot-4 and 118 pounds — didn’t have the physical strength to operate the stiff controls. His actions violated safety protocols, but, of course, he was never punished. Ratting on a superior officer was something you didn’t do, unless you didn’t care about finishing flight school, and I wanted to fly.

Not all Navy men were bad actors. Many with whom I worked respected me and I them. Once, when I was being attacked in my dorm room by a large, drunken enlisted man, my male coworkers pulled him off of me. On another occasion, when a higher-ranking mission commander made sexually inappropriate comments to me, my aircrewmen helped me buy a prostitute to visit his hotel room. That angered my taunter, but he never learned who paid for the woman. The men who served under my command were loyal. Then, when the same commander got into a bar fight in a sleazy joint in Lisbon, I came to his defense and pulled the attacker’s hair back so the commander could defend himself. My men loved it, but the ungrateful commander scolded me for not breaking a bottle and cutting the attacker.

As a senior Naval officer in the reserves, I was kidnaped in Dakar, Senegal, when I got into a taxi cab that was supposed to take me to the embassy, where I would deliver a report. The driver locked the doors and drove me to a remove area outside of the city. I escaped. An investigation by the military attaché and CIA revealed that the cab driver had planned to take me to a white slave trade camp.

After leaving the Navy and obtaining a job as a commercial airline pilot, I was hospitalized for trauma for a brief time. I felt unmoored. For a decade I had been surrounded by Navy people who, despite some bad actors, I considered to be part of my family. Now that was gone. Airline pilots rarely fly with the same colleagues, and aside from brief sessions in the crew room before flights, rarely socialize with each other. Most people think being a pilot is a glamorous job. But it’s a lonely life if you don’t have a family to go home to. I recovered from my illness after a compassionate doctor helped me address my childhood traumas.

As an airline pilot, I tolerated chauvinistic glances and whispers from some passengers who were uneasy that a woman was flying their plane. Of course, there’s no logical reason why women should be less capable of flying a plane than a man. Research even shows that male pilots have a higher rate of crashes. On one occasion in Dubia, I had to assume control of a Boeing 747 cargo plane after the male captain froze when one of the landing gear didn’t fully extend on final approach. After landing, the all-male United Arab Emirate authorities questioned the veracity of my story, simply because I was a woman.

When I was younger, I thought I would see the end of sexism in my lifetime. The women’s movement and Equal Rights Amendment held so much promise. But I was wrong. Deep-seated gender biases — and racial and identity biases, too — are extremely difficult to eradicate, as recent political events in America continue to show. That’s why stories like mine are still relevant. There’s no place for second-class citizenship in America.

Adversity and discrimination often destroy people and lives. Some of my female flight trainee colleagues dropped out because they couldn’t take the abuse. I felt sorry for them.

But adversity can also build character. Every time a man told me I wasn’t good enough, smart enough, or strong enough, I worked harder. Adversity made me stronger and prepared me not only for the in-flight emergency I was now facing, but for other challenges, including a Navy SEAL who screamed at me during my first week of Officer Candidate School.

Chapter 2

Officer Candidate School

January 12, 1977

Navy Officer Candidate School

Newport, Rhode Island

The oversized Adam’s apple on my 6-foot-tall beefy Navy SEAL room inspector is six inches away from my face and is bobbing up and down like a parakeet on steroids. He’s yelling at me because he found a granola bar hidden in one of my panties.

“Hiding food is a serious violation of inspection rules, CUMIN,” the former Vietnam veteran screams. A CUMIN is a Civilian Under Military Instruction — a pejorative acronym in this context. “Do you understand that, CUMIN? You are unworthy to be a Naval officer. You are scum. You are CUMIN scum.”

I dare not take my eyes off his undulating laryngeal prominence, because I’ve seen all of the movies about what drill inspectors do to recruits who fail to cage their eyes, and I’m allergic to pealing potatoes and cleaning toilets. But amusement, not fear, is the emotion I’m feeling right now. I never thought a bobbing apple could be so funny, and I’m trying with all my might to contain a full-bellied laugh.

“You are filthy scum, CUMIN. You are a disgrace to ... ”

Up, down. Up, down.

My roommate, Leslie, is standing at attention next to me. She and I both hid food in our underwear, because we would get hungry outside of mess hall hours. We assumed the inspectors wouldn’t probe our personal garments. After all, that would be an invasion of privacy or an act of perversion.

Leslie is 6-foot-2, so if the SEAL were yelling at her, she would be eye-to-eye and wouldn’t have to look at his pulsating distended blood vessels. But I’m only 5-4 — a captive to the apple of my eye.

Up, down. Up, down.

Some psychologists argue that humor results when an innocuous norm or rule has been violated. To me, being chewed out for hoarding a granola bar clearly fit this criterion. The Navy surely wouldn’t want its recruits to be undernourished. But rules are rules, sociologists point out, even when they fail to achieve a goal.

Up, down. Up, down.

I can’t take this anymore.

When I erupt with laughter, the SEAL yells even louder, which makes me laugh even more. Then he stops shouting and I swiftly suppress my guffaw. He purses his lips, pivots, and marches into the hallway, where he calls for other SEAL inspectors. I hear barking and moaning sounds, but I can’t make out the words.

Will this be my last day of officer-training school?

Doors slam and silence fills the hallway.

Leslie and I don’t know what to do. We stand at attention for several minutes, until we hear soft female voices coming the room next door. I peer into the hallway. The SEALS have slipped away.

“You’re in big trouble,” Leslie says.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, contact David Demers at [email protected] or call 623-363-4668.

Fire in the Sky

10:20 a.m, Sunday, June 11, 2000

US Airways Flight 70

San Francisco to Philadelphia

Over the California-Nevada border

My copilot, Arnie, had just leveled our Airbus 319 to a cruising altitude 37,000 feet in a serene powder-blue sky when an alarm screeches and a red master switch flashes a warning message that the aft cargo compartment is on fire.

We glance at each other.

Is the warning light malfunctioning or is there a fire?

We have no access to the cargo area and it has no cameras.

We pitch our breakfast trays to the flight deck behind us, reach down on the outside of our seats, and extract and don our full face oxygen masks. My thoughts drift to the flash fires that brought down ValuJet and Swiss Air airliners several years earlier. All 339 passengers and crew aboard those two flights died. At this altitude, we would need at least 15 minutes to land the plane. A fire can do a lot of damage in that time.

From the captain’s seat on the left side, I swiftly raise my right hand and press an overhead panel button that activates the aft cargo fire extinguisher, which is designed to flood the room with Halon gas. I hold my breath, waiting to see if the warning light will go out. My heart is pounding faster than normal, but I feel no panic. I’ve been through hundreds of emergency drills before in simulators and a few real ones in the air. I’m 47 and have been a commercial airline pilot for eleven years. I learned to fly in the Navy and was one of the first women to earn her Navy Wings of Gold in 1980.

Arnie is cool-headed, too. Former Marine Corps pilots are like that. He gives me one of those let’s-hope-this-works looks. He’s in his forties and had been a Marine pilot for twenty years, including four years as captain of Marine One, the helicopter that ferried Presidents George H. W. Bush and Bill Clinton to and from the White House. Arnie has about a year’s experience as a commercial pilot. He’s piloting this leg of the trip.

The fire warning light finally goes out.

We remove our masks and take a deep breath, but the emergency isn’t over. The fire could flare again, so I instruct Arnie to “prepare to get the plane down.”

As he programs the autopilot for descent, I hail Oakland Air Route Traffic Control Center. “US Airways Flight 70 is declaring an emergency. We just extinguished a fire in our aft cargo but need to land.”

“Reno [airport] is the closest,” the control center responds. “Just off to your left and pretty much right below you — thirty-seven to forty miles away.”

“Okay, we’ll go there.”

“Turn left heading 3-4-0. Cleared to 24,000 feet.”

Arnie sets the descent at 6,000 feet per minute. That’s twice as fast as normal. Gravity is going to suck passengers forward against their seat belts, frightening some.

I push a call button, and Terri, the lead flight attendant, opens the door and leans her slim body toward me. “What’s up?” Her job is to keep the passengers calm, but I don’t want to alarm her, because she is a recently hired flight attendant and I don’t how she performs under stress. The lead flight attendant job is often given to lesser-experienced attendants, because the work load is heavier and experienced attendants feel entitled. So I soft-pedal the emergency to Terri.

“We’re making a divert into Reno to have the pressurization system looked at before going over the Rocky Mountains. We are going to descend quickly and the landing should be normal. Prep for landing.”

Terri is calm, and her simple, noninquisitive response — “I understand” — reassures me.

I brief the passengers over the intercom. “This is the captain. We are making a precautionary diversion to Reno — just off to our left — to have our pressurization system checked before flying over the Rockies. Sorry for the delay. It shouldn’t take long to check out our concern and get underway again.”

I stretched the truth a little. It likely will take a while to install a new fire extinguisher system, but my main concern is to prevent the passengers from panicking.

Arnie monitors our descent and I enter the code letters for Reno into the computer to obtain dynamic approach and landing feedback information. I’m concerned about the mountains on the west side of the airport, but the computer won’t accept my entry. So I pull out the Jeppesen approach plate book, which provides a visual representation of landing approaches at airports. Nothing there, either.

“Damn! Mountains and no approach plates. The airline must consider Reno such a poor divert alternative that they didn’t even include it in the binder.”

Arnie frowns. I don’t know whether he’s reacting to the lack of information about the landing approach, to my frustration, or both. This is my first trip with him. He is a man of few words. I like that.

I turn my attention to completing the approach checklist.

Air traffic control clears us to go to 11,000 feet, which is 500 feet above the minimum safe altitude to clear the mountains. Arnie then resets the autopilot to descend at 2,000 feet per minute. The approach to the airport is three minutes away.

But a minute later, at about 15,000 feet, a chime sounds and an amber warning light flashes on the panel: OIL FILTER CLOGGED. Before Arnie and I can process that message, another amber warning light appears: LOW OIL PRESSURE. Yet the oil pressure indicator gauge is green, not amber or red, which means that even if the filter is clogged, oil apparently is getting to the engine through a bypass.

Shit — two emergencies almost never happen at the same time.

“Arnie, what’s happening? The warnings don’t make sense.”

“Temps and pressures are okay,” he says. “No vibration, no unusual noise. Do you see anything, Carole?”

“Nothing you don’t. Maybe we could bring the engine to idle — keep it running in reserve for more power over the mountains if we have to go around for a second approach.”

Arnie’s dark brown eyes narrow. “Carole, my best guess is that the filter bypasses are clogged and the engine’s not getting oil. It’s telling us to shut it down so it doesn’t seize and explode.”

“Well, we’re not a thousand miles out over the ocean,” I say, thinking out loud, “and we’re so high and close that we more than have the field made, and we can fly single engine. Okay, let’s shut it down. Arnie, I know it’s your leg, but I’ll take the aircraft.”

“I agree we should shut the engine down.” He pauses. “Carole, you’re the captain, but I have a lot more time in the Airbus. Are you sure you want to take it?”

“Yeah, I’m sure.”

Arnie does have more time flying the A319 than I do. But I have far more experience flying commercial airliners, including the wide-bodied Boeing 767, and I have spent years instructing pilots in simulators and in the air. Besides, the captain is ultimately responsible for her airship. I’m not going to shirk my responsibility.

“Okay, Captain, you have the aircraft.”

We go through the shutdown procedure for the left engine. I guard the right engine power lever with my right hand. When pilots are under stress, they sometimes make mistakes. My job is to ensure Arnie doesn’t shut down the good engine. He grasps the left engine power lever, and we confirm three times that we are shutting down the correct engine.

I compensate for a slight yaw to the left that occurs when an engine is shut down. The transition is seamless, as if nothing had happened.

I call Reno Air Traffic Control. “This is US Airways Flight 70 declaring a full emergency. We had to shut down the left engine.”

“How many Souls on Board? And how much fuel?”

Controllers who use the term “souls” violate FAA guidelines, which recommends “people,” but this is no time to debate that point. A captain also is supposed to report fuel levels in hours of flight time, but I don’t have time to do the calculations.

“I have 108 passengers, six crew, and 40,000 pounds of fuel.”

“OK, you should see Reno right in front of you.”

Arnie and I had been too busy to visually locate the airport. Now I can see the far end of the runway, just beyond the crest of the mountain we are passing over. But the runway is still 6,000-feet below us.

“Oh shit!” I mutter. “We’re way too high.”

Arnie frowns again.

“Let’s sidestep,” I say, loosening my starched white collar. “I’ll reduce airspeed. Looks like no mountains at the north end, so we should be able to turn around and land going back south, the same way we came in.”

Arnie nods.

The airport has two parallel north-south runways. The one on the west, when landing south, is 17R and is 11,000-feet long. The east one is 17L and 9,000 feet. I want the west-side runway so I can see out the side cockpit window and use the east runway as a guide for landing. Besides, 17R is longer. We may need the extra space.

Arnie hails the control tower and requests 17R, but the tower wants us to use the left runway.

“No, we’re going right!” Arnie says firmly.

The tower concedes.

I smile. Nice to have a Marine as a first officer. During emergencies, ground control must defer to pilots. Reno’s responsibility is to clear the runway of aircraft and get the emergency vehicles ready.

I grasp the side stick flight control with my left hand and switch off the autopilot. Without computerized feedback about the airport, Arnie and I will have to decide on an appropriate airspeed and rate of descent. I manually adjust the rudder trim again to compensate for the uneven push due to flying on one engine. I lower the landing gear and flaps and begin doing S-turns to slow airspeed. No time to tell the passengers what’s happening.

My biggest concern is stopping the plane after we land. Fully loaded, the A319 needs about seven-thousand feet of runway, which is four thousand less than the length of R17. But we only have one reverse thruster to slow our speed, and we’re heavy with fuel. Will the tires hold up when we brake?

Our plane’s radar altimeter now shows we’re 2,300 feet above the ground.

“Arnie, ask them if there’s a VASI at the north end of the runway.” A visual approach slope indicator is a color-coded runway lights system that shows whether the aircraft is on the correct landing approach with the preferred three-degree glide slope.

“Yes, there’s a VASI,” the tower responds.

Arnie and I conclude that our best landing speed is 150 knots, slightly faster than normal, because we’re heavy with fuel and because we can only use 20 degrees of flaps instead of 30. At this weight, the drag with 30 would be too much and we’d have to use a faster landing speed. We don’t want to run out of runway.

Just past the north end of the runway, I make a U-turn and line up with 17R. VASI lights are red over white, indicating our glide path is perfect.

Runway coming up.

On centerline.

I can feel my heart pounding in my fingertips.

Touching down ...

* * * * *

A popular trope says your life flashes before you when you’re in a near-death situation.

Although I was confident I could safely land Flight 70, I couldn’t help but reflect for a moment on my past.

My childhood was difficult. I had a mother who often beat me and shut me into a closet; a brother who stabbed his psychiatrist and tried to attack me; and a cold-hearted father who refused to allow me to join him for Thanksgiving dinner one year. One of my mother’s boyfriend’s sexually abused me when I was a girl. When I was promoted to captain, my father never congratulated me. Perhaps he envied me, as he had only achieved the rank of commander.

My grandfather was one of the few loving people in my life. He had been a Navy pilot and admiral and had earned the Navy Cross for bringing to port his ship, the U.S.S. Kearny, after a German U-boat torpedoed it two months before the United States entered World War II.

My life in the Navy wasn’t easy in the early years. One enlisted man tried to rape me. Some superior officers made passes at me and stalked me. On three occasions men accused me of wrongdoing, including the heinous act of typing up Christmas carols on a base typewriter.

As a pilot in training, some male flight instructors tried to derail my career. “You’ll never be as good as we are,” one said. Another instructor shut down the hydraulic system on a plane during final approach in an attempt to prove that I — at 5-foot-4 and 118 pounds — didn’t have the physical strength to operate the stiff controls. His actions violated safety protocols, but, of course, he was never punished. Ratting on a superior officer was something you didn’t do, unless you didn’t care about finishing flight school, and I wanted to fly.

Not all Navy men were bad actors. Many with whom I worked respected me and I them. Once, when I was being attacked in my dorm room by a large, drunken enlisted man, my male coworkers pulled him off of me. On another occasion, when a higher-ranking mission commander made sexually inappropriate comments to me, my aircrewmen helped me buy a prostitute to visit his hotel room. That angered my taunter, but he never learned who paid for the woman. The men who served under my command were loyal. Then, when the same commander got into a bar fight in a sleazy joint in Lisbon, I came to his defense and pulled the attacker’s hair back so the commander could defend himself. My men loved it, but the ungrateful commander scolded me for not breaking a bottle and cutting the attacker.

As a senior Naval officer in the reserves, I was kidnaped in Dakar, Senegal, when I got into a taxi cab that was supposed to take me to the embassy, where I would deliver a report. The driver locked the doors and drove me to a remove area outside of the city. I escaped. An investigation by the military attaché and CIA revealed that the cab driver had planned to take me to a white slave trade camp.

After leaving the Navy and obtaining a job as a commercial airline pilot, I was hospitalized for trauma for a brief time. I felt unmoored. For a decade I had been surrounded by Navy people who, despite some bad actors, I considered to be part of my family. Now that was gone. Airline pilots rarely fly with the same colleagues, and aside from brief sessions in the crew room before flights, rarely socialize with each other. Most people think being a pilot is a glamorous job. But it’s a lonely life if you don’t have a family to go home to. I recovered from my illness after a compassionate doctor helped me address my childhood traumas.

As an airline pilot, I tolerated chauvinistic glances and whispers from some passengers who were uneasy that a woman was flying their plane. Of course, there’s no logical reason why women should be less capable of flying a plane than a man. Research even shows that male pilots have a higher rate of crashes. On one occasion in Dubia, I had to assume control of a Boeing 747 cargo plane after the male captain froze when one of the landing gear didn’t fully extend on final approach. After landing, the all-male United Arab Emirate authorities questioned the veracity of my story, simply because I was a woman.

When I was younger, I thought I would see the end of sexism in my lifetime. The women’s movement and Equal Rights Amendment held so much promise. But I was wrong. Deep-seated gender biases — and racial and identity biases, too — are extremely difficult to eradicate, as recent political events in America continue to show. That’s why stories like mine are still relevant. There’s no place for second-class citizenship in America.

Adversity and discrimination often destroy people and lives. Some of my female flight trainee colleagues dropped out because they couldn’t take the abuse. I felt sorry for them.

But adversity can also build character. Every time a man told me I wasn’t good enough, smart enough, or strong enough, I worked harder. Adversity made me stronger and prepared me not only for the in-flight emergency I was now facing, but for other challenges, including a Navy SEAL who screamed at me during my first week of Officer Candidate School.

Chapter 2

Officer Candidate School

January 12, 1977

Navy Officer Candidate School

Newport, Rhode Island

The oversized Adam’s apple on my 6-foot-tall beefy Navy SEAL room inspector is six inches away from my face and is bobbing up and down like a parakeet on steroids. He’s yelling at me because he found a granola bar hidden in one of my panties.

“Hiding food is a serious violation of inspection rules, CUMIN,” the former Vietnam veteran screams. A CUMIN is a Civilian Under Military Instruction — a pejorative acronym in this context. “Do you understand that, CUMIN? You are unworthy to be a Naval officer. You are scum. You are CUMIN scum.”

I dare not take my eyes off his undulating laryngeal prominence, because I’ve seen all of the movies about what drill inspectors do to recruits who fail to cage their eyes, and I’m allergic to pealing potatoes and cleaning toilets. But amusement, not fear, is the emotion I’m feeling right now. I never thought a bobbing apple could be so funny, and I’m trying with all my might to contain a full-bellied laugh.

“You are filthy scum, CUMIN. You are a disgrace to ... ”

Up, down. Up, down.

My roommate, Leslie, is standing at attention next to me. She and I both hid food in our underwear, because we would get hungry outside of mess hall hours. We assumed the inspectors wouldn’t probe our personal garments. After all, that would be an invasion of privacy or an act of perversion.

Leslie is 6-foot-2, so if the SEAL were yelling at her, she would be eye-to-eye and wouldn’t have to look at his pulsating distended blood vessels. But I’m only 5-4 — a captive to the apple of my eye.

Up, down. Up, down.

Some psychologists argue that humor results when an innocuous norm or rule has been violated. To me, being chewed out for hoarding a granola bar clearly fit this criterion. The Navy surely wouldn’t want its recruits to be undernourished. But rules are rules, sociologists point out, even when they fail to achieve a goal.

Up, down. Up, down.

I can’t take this anymore.

When I erupt with laughter, the SEAL yells even louder, which makes me laugh even more. Then he stops shouting and I swiftly suppress my guffaw. He purses his lips, pivots, and marches into the hallway, where he calls for other SEAL inspectors. I hear barking and moaning sounds, but I can’t make out the words.

Will this be my last day of officer-training school?

Doors slam and silence fills the hallway.

Leslie and I don’t know what to do. We stand at attention for several minutes, until we hear soft female voices coming the room next door. I peer into the hallway. The SEALS have slipped away.

“You’re in big trouble,” Leslie says.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, contact David Demers at [email protected] or call 623-363-4668.

New from Marquette Books

AN EPIC LIFE AND POEM

By the time of his death in Babylon on June 10, 323 BC, Alexander the Great had conquered more than two million square miles and was only thirty-two years of age.

He was an intrepid Macedonian warrior, superb strategist and masterful diplomat. He accepted and respected other peoples, cultures, treated women with dignity, and was exceptionally considerate of the disabled. He loved animals, large and small, domesticated and wild. His legacy is felt all over the world.

This slim volume serves as an introduction to Alexander, hoping to whet your appetite and lure you into a more extensive and deeper investigation of the questions that still resonate from his meteoric rise and mysterious demise. What follows is a lyrical biography -- the first poem covering his life from birth to death since the nineteenth century. The poem is simple and unadorned, readable and rooted in historical research. It was written for curious teenagers as well as lifelong learners.

This 390-stanza, lyrical biographical poem about Alexander the Great is accompanied by 48 illustrations, most in full color, including a map of his military advances and victories.

Alexander the Great: A Lyrical Biography

By Christine O'Brien and John Maxwell O'Brien

128 pp, 6 x 9 format, $24.95 (ISBN 978-1-7327197-4-3)

Library of Congress Control Number 2021953111

Also available in e-book (ISBN: 978-1-7327197-3-6, $7.99)

Christine O’Brien holds an honors degree in classical civilization from Boston College. This epic poem constitutes her literary debut. John Maxwell O’Brien is an emeritus professor of history at Queens College (CUNY). His best-selling biography, Alexander the Great: The Invisible Enemy, has been translated into Greek and Italian.

Publication Date: July 20, 2022, Alexander's 2,377th Birthday

Distributed by Ingram Book Company

Worldwide Praise

"Through their brilliant and gripping labyrinth of lyrics, the authors take us on a journey into the realm of the remarkable life of Alexander the Great. Simply mesmerizing." –Shameela Yoosuf Ali is an artist, writer and Editor-In-Chief of FemAsia Magazine (UK)

"This epic poem will prove to be a precious resource for high school and university teachers who wish to keep antiquity alive. A real gem." –Erik Martiny, a novelist, translator and academic who teaches at the Lycée Henri IV in Paris

"An outstanding book: well-written for both adults and children, with meticulously chosen illustrations." –Sven Kretzschmar, a German poet who publishes in English and German

"This glorious book is interwoven with history, richness and illuminating light." –Annemarie Ní Churreáin, an Irish poet, writer and author of The Poison Glen (The Gallery Press, 2021)

"A marvelous book that will excite and enlighten readers of all ages." –Salhi Lazhar Ben Larbi, a teacher of history and geography in Algeria

"The O'Briens have narrated the life and times of Alexander in an artfully crafted ballad reminiscent of Samuel Taylor Coleridge!" –Mark Ulyseas, publisher/editor of Live Encounters Magazines (India)

"In every line a double heartbeat, history teeming in the blood, each stanza wrapped in lyric, alive again the fallible Alexander, a hero unmasked, his story told." –James Walton, an Australian poet and fiction writer whose works have been translated into multiple languages

He was an intrepid Macedonian warrior, superb strategist and masterful diplomat. He accepted and respected other peoples, cultures, treated women with dignity, and was exceptionally considerate of the disabled. He loved animals, large and small, domesticated and wild. His legacy is felt all over the world.

This slim volume serves as an introduction to Alexander, hoping to whet your appetite and lure you into a more extensive and deeper investigation of the questions that still resonate from his meteoric rise and mysterious demise. What follows is a lyrical biography -- the first poem covering his life from birth to death since the nineteenth century. The poem is simple and unadorned, readable and rooted in historical research. It was written for curious teenagers as well as lifelong learners.

This 390-stanza, lyrical biographical poem about Alexander the Great is accompanied by 48 illustrations, most in full color, including a map of his military advances and victories.

Alexander the Great: A Lyrical Biography

By Christine O'Brien and John Maxwell O'Brien

128 pp, 6 x 9 format, $24.95 (ISBN 978-1-7327197-4-3)

Library of Congress Control Number 2021953111

Also available in e-book (ISBN: 978-1-7327197-3-6, $7.99)

Christine O’Brien holds an honors degree in classical civilization from Boston College. This epic poem constitutes her literary debut. John Maxwell O’Brien is an emeritus professor of history at Queens College (CUNY). His best-selling biography, Alexander the Great: The Invisible Enemy, has been translated into Greek and Italian.

Publication Date: July 20, 2022, Alexander's 2,377th Birthday

Distributed by Ingram Book Company

Worldwide Praise

"Through their brilliant and gripping labyrinth of lyrics, the authors take us on a journey into the realm of the remarkable life of Alexander the Great. Simply mesmerizing." –Shameela Yoosuf Ali is an artist, writer and Editor-In-Chief of FemAsia Magazine (UK)

"This epic poem will prove to be a precious resource for high school and university teachers who wish to keep antiquity alive. A real gem." –Erik Martiny, a novelist, translator and academic who teaches at the Lycée Henri IV in Paris

"An outstanding book: well-written for both adults and children, with meticulously chosen illustrations." –Sven Kretzschmar, a German poet who publishes in English and German

"This glorious book is interwoven with history, richness and illuminating light." –Annemarie Ní Churreáin, an Irish poet, writer and author of The Poison Glen (The Gallery Press, 2021)

"A marvelous book that will excite and enlighten readers of all ages." –Salhi Lazhar Ben Larbi, a teacher of history and geography in Algeria

"The O'Briens have narrated the life and times of Alexander in an artfully crafted ballad reminiscent of Samuel Taylor Coleridge!" –Mark Ulyseas, publisher/editor of Live Encounters Magazines (India)

"In every line a double heartbeat, history teeming in the blood, each stanza wrapped in lyric, alive again the fallible Alexander, a hero unmasked, his story told." –James Walton, an Australian poet and fiction writer whose works have been translated into multiple languages